Recently, the awesome-lisp-companies list was posted on HN, more people got to know it (look, this list is fan-cooked and we add companies when we learn about one, often by chance, don’t assume it’s anything “official” or exhaustive), and Alex Nygren informed us that his company Kina Knowledge uses Common Lisp in production:

We use Common Lisp extensively in our document processing software core for classification, extraction and other aspects of our service delivery and technology stack.

He very kindly answered more questions.

Thanks for letting us know about Kina Knowledge. A few more words if you have time? What implementation(s) are you using?

We use SBCL for all our Common Lisp processes. It’s easier with the standardization on a single engine, but we also have gotten tied to it in some of our code base due to using the built in SBCL specific extensions. I would like, but have no bandwidth, to evaluate CCL as well, especially on the Windows platform, where SBCL is weakest. Since our clients use Windows systems attached to scanners, we need to be able to support it with a client runtime.

Development is on MacOS with Emacs or Ubuntu with Emacs for CL, and then JetBrains IDEs for Ruby and JS and Visual Studio for some interface code to SAP and such. We develop the Kina UI in Kina itself using our internal Lisp, which provides a similar experience to Emacs/SLY.

What is not Lisp in your stack? For example, in “Kina extracts information from PDF, TIFFs, Excel, Word and more” as we read on your website.

Presently we use a Rails/Ruby environment for driving our JSON based API, and some legacy web functions. However, increasingly, once the user is logged in, they are interacting with a Common Lisp back end via a web socket (Hunchentoot and Hunchensocket) interacting with a Lisp based front end. Depending on the type of information extraction, the system uses Javascript, Ruby and Common Lisp. Ideally, I’d like to get all the code refactored into a prefix notation, targeting Common Lisp or DLisp (what we call our internal Lisp that compiles into Javascript).

What’s your position on open-source: do you use open-source Lisp libraries, do you (plan to) open-source some?

Yes. We recently put our JSON-LIB (https://github.com/KinaKnowledge/json-lib) out on Github, which is our internal JSON parser and encoder and we want to open source DLisp after some clean-up work. Architecturally, DLisp can run in the browser, or in sandboxed Deno containers on the server side, so we can reuse libraries easily. It’s not dependent on a server-side component though to run.

Library wise, we strictly try and limit how many third party (especially from the NPM ecosystem) libraries we are dependent on, especially in the Javascript world. In CL, we use the standard stuff like Alexandria, Hunchentoot, Bordeaux Threads, and things like zip.

How did hiring and forming lisp or non-lisp developers go? Did you look for experienced lispers or did you seek experienced engineers, even with little to no prior Lisp background?

Because we operate a lot in Latin America, I trained non-lisper engineers who speak Spanish on how to program Lisp, specifically our DLisp, since most customizations occur specifically for user interface and workflows around document centric processes, such as presenting linked documents and their data in specific ways. How the lisp way of thinking really depended on their aptitude with programming, and their English capabilities to understand me and the system. The user system is multilingual, but the development documentation is all in English. But it was really amazing when I saw folks who are experienced with Javascript and .Net get the ideas of Lisp and how compositional it can be as you build up towards a goal.

Besides, with DLisp, you can on the fly construct a totally new UI interaction - live - in minutes and see changes in the running app without the dreadful recompile-and-reload everything cycle that is typical. Instead, just recompile the function (analogous to C-c, C-c in Emacs), in the browser, and see the change. Then these guys would go out and interact with clients and build stuff. I knew once I saw Spanish functions and little DSLs showing up in organizational instances that they were able to make progress. I think it is a good way to introduce people to Lisp concepts without having to deal with the overhead of learning Emacs at the same time. I pushed myself through that experience when I first was learning CL, and now use Emacs every day for a TON of work tasks, but at the beginning it was tough, and I had to intentionally practice getting to the muscle memory that is required to be truly productive in a tool.

How many lispers are working together, how big a codebase do you manage?

Right now, in our core company we have three people, two here in Virginia and one in Mexico City. We use partners that provide services such as scanning and client integration work. We are self-funded and have grown organically, which is freeing because we are not beholden to investor needs. We maintain maximum flexibility, at the expense of capital. Which is OK for us right now. Lisp allows us to scale dramatically and manage a large code base. I haven’t line counted recently, but it exceeds 100K lines across server and client, with > 50% in Lisp.

Do you sometimes wish the CL (pro) world was more structured? (we have a CL Foundation but not so much active).

I really like the Common Lisp world. I would like it to be more popular, but at the same time, it is a differentiator for us. It is fast - our spatial classifier takes only milliseconds to come to a conclusion about a page (there is additional time prior to this step due to the OpenCV processing - but not too much) and identify it and doesn’t require expensive hardware. Most of our instances run on ARM-64, which at least at AWS, is 30% or so cheaper than x86-64. The s-expression structures align to document structures nicely and allow a nice representation that doesn’t lose fidelity to the original layouts and hierarchies. I am not as active as I would like to be in the Common Lisp community, mainly due to time and other commitments. I don’t know much about the CL foundation.

And so, how did you end up with CL?

Our UI was first with the DLisp concepts. I was intrigued by Clojure for the server portion, but I couldn’t come to terms with the JVM and the heavyweight of it. The server-side application was outgrowing the Rails architecture in terms of what we wanted to do with it, and, at the time, 4 years ago, Ruby was slower. In fact, Ruby had become a processing bottleneck for us (though I am certain the code could have been improved too). I liked the idea of distributing binary applications as well, which we needed to do in some instances, and building a binary runtime of the software was a great draw, too.

I also liked how well CL is thought out, from a spec standpoint. It is stable both in terms of performance and change. I had been building components with TensorFlow and Python 3, but for what I wanted to do, I couldn’t see how I could get there with back propagation and the traditional “lets calculate the entire network state”. If you don’t have access to high end graphic cards, it’s just too slow and too heavy. I was able to get what we needed to do in CL after several iterations and dramatically improve speed and resource utilization. I am very happy with that outcome. We are in what I consider to be a hard problem space: we take analog representations of information, a lot of it being poor quality and convert it to clean, structured digital information. CL is the core of that for us.

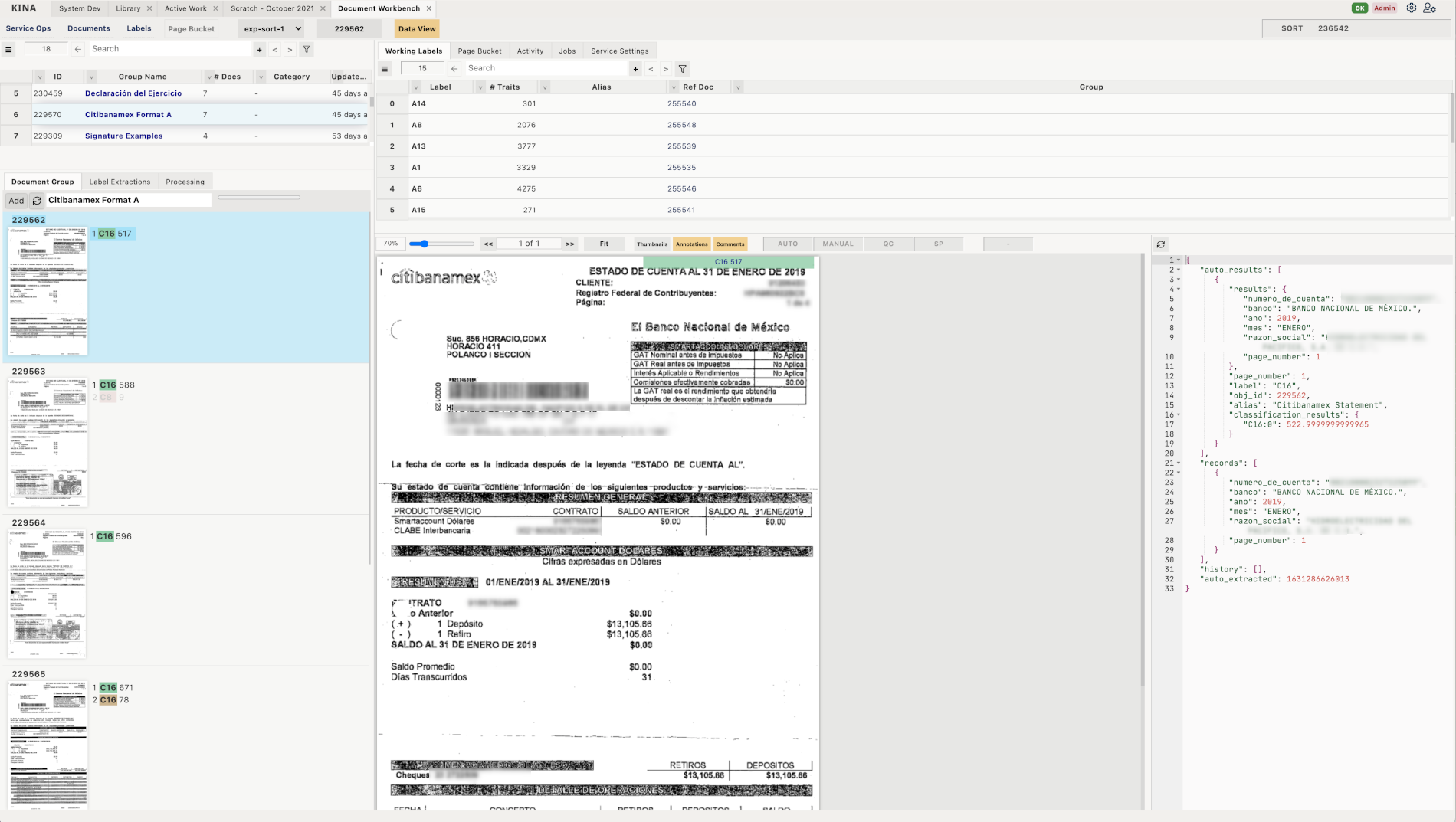

Here is an example of our UI, where extractions and classification can be managed. This is described in DLisp which interacts with a Common Lisp back end via a web socket.

Here is the function for the above view being edited in Kina itself. We do not obfuscate our client code, and all code that runs on our clients’ computers is fully available to view and, with the right privileges, to modify and customize. You can see the Extract Instruction Language in the center pane, which takes ideas from the Logo language in terms of a cursor (aka the turtle) that can be moved around relative to the document. We build this software to be used by operations teams and having a description language that is understandable by non-programmers such as auditors and operations personnel, is very useful. You can redefine aspects of the view or running environment and the change can take effect on the fly. Beyond the Javascript boot scaffolding to get the system started up in the browser, everything is DLisp communicating with Common Lisp and, depending on the operation, Rails.

I hope this information is helpful!

It is, thanks again!